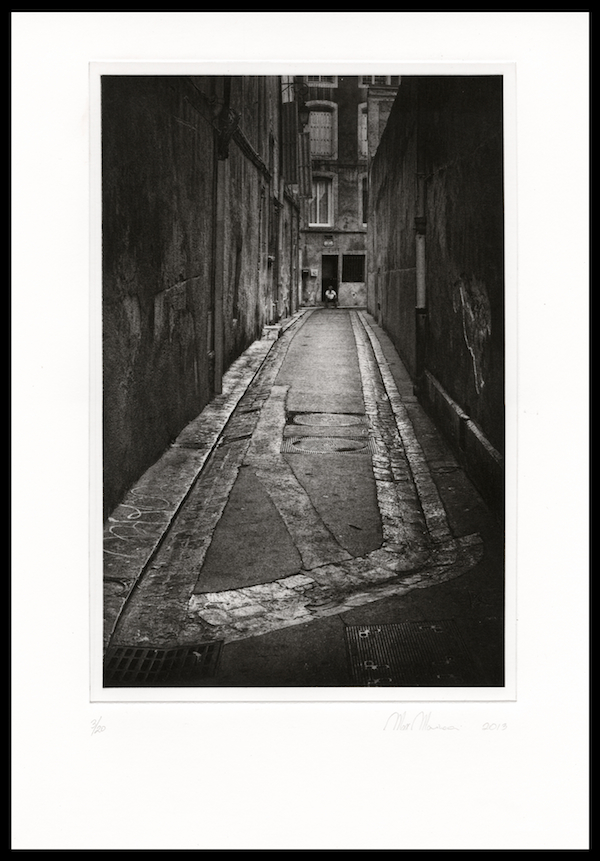

“Down The Drain”

The Future Is In The Past – The Leica Monochrom and Photogravure

Max Marinucci Photography

Fine Art Photography

Silver Gelatin and Photogravure

South Salem, NY

As a photographer and printer, I’ve always seen the advent of digital photography as a mixed blessing. The gain in speed, convenience, immediacy, offered by digital photography, also meant the gradual loss of film and everything related to it (photographic paper, chemicals) and, more importantly, the loss of learned skills and knowledge that are needed to produce truly hand-made prints. I have, of course, continued to use film for most of my work and honed my skills producing quality silver gelatin prints, in a world when a photographer feels like he is constantly swimming against the digital current. Kodak is no longer a driving force and so many manufacturers have disappeared or stopped making photographic product, with Ilford being the only reliable and consistent source as of today. Over the past year, while still dedicated to film photography and silver gelatin, I’ve rediscovered what is the most venerable, and in my opinion most beautiful of photographic processes: photogravure. A venerable process, and a 19th century invention, it was indeed how photography came to life, on paper, at the dawn of it all. On the camera front, as a devoted Leica user, I’ve continued with my trusty M3 and later film incarnations as the M4, M6, M7 and MP, until finally breaking down and acquiring a Monochrom upon release. There was no denying that the allure of a no fuss, great Leica camera that captures images in black and white only was too much to bear but, as my personality dictates, everything has to have a clear purpose. I am not an inkjet printer and I see no purpose in spending a good chunk of hard-earned cash on a camera to simply post digital snapshots on social networks or photography related websites, in a vacuum, with a purely digital workflow. As a photographer, artist and a printer, how do I justify the investment and, better yet, how do I bring the amazingly detailed images that the Monochrom is able to record, to life, on paper? Marrying our historic photographic past to the latest in technology, in a seamless way, and one that offers the viewer, collector, buyer, a tangible product that is not mass-produced but it is a handmade work of art, seemed the one and only way for me.

The Leica Monochrom and Photogravure: the future is in the past.

“The Old Man By The Window”

Because of technological advances within the printing industry, and pioneers such as Jon Cone of Piezography, Roy Harrington of QTR, and Mark Nelson of Precision Digital Negatives (and few others) today it is possible to print absolutely flawless digital positives to use for the photogravure process. Of course, that doesn’t make this amazing process any easier, as it still involves the same numerous (and full of pitfalls) steps as it did one hundred years ago, but one only needs to admire in person the incredible prints born from Leica Monochrom images and onto fine art papers, hand-made with beautiful inks, to realize how special this is. I firmly believe that for a fine art photographer and printer, who is willing to let go of the constant film versus digital battles and discussions, these can be exciting times, if only one is willing to learn and push the boundaries a bit. For my own work it has now come to a point when shooting film with the ultimate goal of making photogravure plates and prints is almost not worth it. Of course, medium and large format film still offer many possibilities but, at the end of the day, film still has to be scanned and that will always be the weakest link (and probably weaker as we go on, as film scanners are barely in production). While results can be more than acceptable with 35mm, and I will still continue on this path on occasion, the amount of detail and the possibilities available with the Leica Monochrom and photogravure are truly exciting and special.

“Porte, Cassis”

For the novice who may be wondering why go through the trouble of using such a cumbersome and antiquated process to produce a print, I’d like to again outline a few important points: obviously, for as beautiful as the best inkjet prints may be, there are no particular skills required and no “hands on” aspect. If one enjoys actually “making” something, an inkjet print gives no satisfaction. Then there is the aspect of the print itself. With inkjet, we have ink (and a crappy one in most cases), sitting on top of the paper. With photogravure etchings, the image is IN the paper. What does that mean? Well, an etching on copper is basically peaks and valleys. The valleys are the deep crevices, which hold more ink and create the deep shadows and blacks, and the peaks will hold much less and create the highlights in print. Of course, we have everything in between, for a true full range of tones. What this does is actually creating a relief on paper. The images have a structure and depth that one cannot replicate with an inkjet printer, or with any other process.

“Strength and Grace”

The Prints:

All prints are in editions of 20, with image size 12×8 for standard 35mm format and 8×8 for square crops. Printed on Magnani Revere or Somerset papers, using Graphic Chemicals, Charbonnelle, and Izote etching inks. Of course archival qualities far exceed those of inkjet prints and even silver gelatin. Every print is hand made by me, and hand pulled using a manual etching press. Aside from the original digital file and the production of a “positive” on clear film, the process is fully analog.

A word about the Photogravure process:

Please do note that when I say photogravure, I mean, “copper-plate photogravure”. There is another printing process that uses pre-sensitized “polymer” plates and a few “artists” have gotten into the habit of calling it simply “photogravure”. It is NOT the same thing! Copper plate photogravure, is an etching process. A gelatin resist that is first sensitized in potassium dichromate is exposed (using first an aquatint screen or rosin dust), then applied to a sheet of mirror finish copper, developed and finally “etched” in a series of ferric chloride acid baths. The Photo-Polymer process is NOT an etching process and it does not require chemicals in any of its steps. It is much easier to master and prints can be absolutely beautiful but…IT IS NOT “PHOTOGRAVURE”.

Lovely article but I must respectfully disagree regarding the assertion that use of photopolymer plates is not an etching process. Anyone who looks into the mechanics of the process will that this is still a process of using a mordant to bite a matrix whether it is copper, zinc, or organic colloid (gum or gelatin) treated with a bichromate. One of the beautiful qualities about moving to photopolymer plates rather than zinc or copper is that you can now use plain old h2o (water) as the mordant rather than some dangerously caustic acid. Thus, photopolymer platemaking affords an option to evolve the practice of plate-making and print-making in a non-toxic direction, and this my friends is something I would think worthy of celebrating, not disparaging. Cheers, Steven

Steven, surprised you revived this old thread, but I understand. Thinking you have joined a club only to have its members assault you, is disturbing.

I am using Imagon HD and making my own plates and have faced the same “you’re not one of us” bigotry. Imagon etches out with an alkali, which of course, “etches” the polymer itself. Technically I suppose I could disparage you because an alkali actually “etches”, while plain water simply erodes.

But welcome anyway. 😉

Come join our photogravure group at yahoo, where we don’t care if you make your plates with chewing gum and watermelons, as long as you get the results:

https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/photogravure/info

As a carbon printers we have the same problem, people calling inkjet prints made with carbon inks-carbon prints. It would be easier if the folks coming up with new methods called them by new names, instead of older established names, just my 2 cents.

Very beautiful prints Max, would you mind sharing the ink/make/type of paper you used on “Down the drain”?

Thanks

Peter

Nice piece.

I have to disagree firmly with the concept of the polymer approach not constituting photogravure. Every time technology advances the old guard tries to claim that the new guard isn’t really doing “the thing”, what ever it is/was. When the first photographers starting using digital equipment, all the old fartz claimed they weren’t “real photographers”. We can see in retrospect, just how silly and petty they sounded.

Photopolymer plates produce photogravures, plain and simple. No special or quasi-deprecating terminology is justified. Polymer plates can either etch just the polymer or go right through to etch a metal plate underneath. The original gravure process was in actuality, just the first kind of “polymer” plate. Gelatin is a polymer folks!!! Coke or Pepsi. Army or Navy.

Photopolymer plates make Photopolymer Intaglio prints not Photogravure prints. Similarly, photo etchings made with a photopolymer resist are not called photogravures, they are called photo etchings. The polymer argument won’t work. In printmaking terminology Photogravure has always meant etching copper with a photo sensitive gelatin resist. Photogravure should not have to distinguish itself from a newer medium now because a few people refuse to be clear about their process. When one sees a print called Photogravure they should be able to know immediately how the print was made, meaning gelatin and copper. This sort of labeling is common in all forms of printmaking, ie. woodcut, linocut, wood engraving etc. All of those prints would be considered relief prints in general but more specifically they are not the same kind of relief print. Rarely will you see a relief print simply labeled ‘Relief’ as printmakers are very process oriented and want to let the viewer know more about how the print was made. Here are more reasons why the two are not the same:

http://www.capefearpress.com/hot-off-the-press.html

So then, following your logic, a plate made with gelatin on aluminum cannot produce a photogravure. A plate made with gelatin on steel cannot produce a photogravure. How about a copper plate later plated with steel? Is that something else too? Gets kinda silly and falls into the same category as photographers using analog materials telling photographers using digital materials that they aren’t real photographers.

And the “polymer argument” does work. Every last chemist on planet Earth will be happy to explain to you that gelatin is a polymer!

On the other hand, I can understand the desire to maintain accuracy and historical continuity. Perhaps “polymer plate photogravure”.

Wonderful pictures.

This is very, very beautiful!

Best regards

Thorkil

and thanks for the effort, that provide our eyes such pleasure, and yes it would have been nice with a lot more pictures, and more Words too.

Thank you, Thorkil, for the kind words. Much appreciated.

Great article Max, really quite inspiring when you read the words of an artisan like yourself as you can really feel the warmth & enthusiasm for your art that you so obviously have. You care, it shows.

I really love that “The Old Man By The Window” photograph too. Sublime.

I was recently reading an article about Peter Turnley and his studying under Bresson and how Turnley still uses Bresson’s master printer Voja Mitrovic and the reasons why. Wonderful stuff!. I started in the darkroom myself as a kid at the age of 13 almost 40 years ago, I only wish I had the time, desire and motivation to extract the highest possible quality from images such as you are doing.

Keep it up Max & please do another article soon. 😉

Thanks so much, my friend. There isn’t much without passion, and I’m glad it shows through my images and writings. Yes, Peter used Voja Mitrovic for years, although I know he’s switched to digital lately so I’m not quite sure of how he prints now. And, it’s never too late..I got back in the darkroom only three years ago and I’m 48. 🙂

Hello Max,

I just forwarded this article’s link to my uncle in France – a B&W photographer who has been very much experimenting with these kind of techniques over the past 30 years – he is going to love it!

Thank you also for your comment about “print being (not) dead” and “being hopelessly romantic,” I can identify.

As a graphic artist (pre-computers) I grew up with strong learnings about the organic aspect of art, be it found in a painting, a print or a beautifully bookbinding (in my case I would even extend such comment to the ‘texture’ of Cinema); the scent, the touch and the viewing payoff can reach levels digital display will never touch.

My sensitivity to this day is unharmed and I’m grateful for that.

For one I would love to see your prints in person and ‘feel’ them, while they are all very beautiful the ‘”Strength and Grace” would actually blow my mind.

Thank you.

Hello Laurent,

Thanks for your note and mostly for your appreciation. These are the kind of conversations that make me feel like all is not yet lost 🙂 it is up to us to teach our children, and anyone willing to listen and learn, the skills necessary to make sure that art does not become simply the gesture of pushing a couple of buttons. There are no substitutes and invariably, when people see wonderful, hand made prints of great images, whether silver gelatin, platinum, gum, collodion, photogravure, etc, they immediately realize what is all about. Unfortunately, in the internet age, we are consuming art in a way that is not conducive to real appreciation, as we move too fast, clicking away, and looking for mere seconds, all for free and with zero sense of value. Holding or hanging a beautiful print lets us ponder, in silence, over time, all there is. And, each time, we may find something new. We cannot abandon this way of appreciating art for the sake of convenience and speed. If we do, we simply give in to accepting a lower standard and embracing mediocrity.

Keep in touch and all my best to you,

Max

For anyone interested in various photographic processes, and their signatures, here is a wonderful link from The Getty Conservation Institute.

http://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/pdf_publications/atlas.html

One of the best articles I´ve read on this very good digi site.I think most of us agree that Mr.Maxi´s handicraft,apart from beeing a lifestyle,is of outmost quality.Some academic word-wrangling does not hide a very serious professional approach to his craft.

Hence forward I´ll be a frequent visitor to the sites of Mr.Steve,Mr Max and Mr.Paul Taylor, in sharing of knowledge and experiance.

Thank you, Juhan, for your kind words. Very happy that you’ve found this stimulating and inspiring.

This post as well as (maybe even more so!) the discussion around it is a huge treasure box. “Thank you” is hardly enough to describe how grateful I am for the information you provided. I always was fascinated by printing processes and never felt like inkjet prints were satisfying my need to create a piece of art enough, but the mystery surrounding processes like photogravure formed a wall that stopped me from looking further. You tore the wall apart and opened a whole new (old) world to me. Thank you.

Thank you, Holger! Very much appreciated. I am happy that I have inspired you to look further into the art of printmaking. Every time this happens, it is a wonderful thing.

Gravure is to engrave, French, from graver, to engrave, from Old French, of Germanic origin.

So if we are going to be pedantic photogravure is also incorrect in its usage of words as when you engrave you do so with a tool and not an acid. But in modern usage engraving now seems to include practices like laser and in some instances acid. I know a silly argument, just like photograph isn’t made with a pencil like a drawing from where the word comes. But it is important that modern usage of language changes as do techniques. This argument is better served in a linguistics department than a blog about digital cameras.

Surely how you make the photogravure (etching or intaglio) plate is irrelevant. The printing process is an identical intaglio process. Both prints are made through the same intaglio process. And in my mind that is essentially what we are talking about and that is a print.

In my mind and to many of the practitioners that the identification needs to be made by the plate. Copper or polymer. I also think we need to identify the creation of the dots (mechanical or digital).

Mind you every coper plate photogravure practitioner I have met is using digitally generated random dot screens, hardly in the traditional method.

Some people will tell you that a platinum print with a digital negative as opposed to a film negative is not a platinum print.

I have been told that my digital images are not photographs too…

So when I print my digital photographs, manipulate them in software, create digital negatives, and create an intaglio plate, that I hand ink and print in an etching press one by one with care and love I am afraid I am going to keep calling them polymer photogravures. Because frankly it really isn’t much different to when I take film photograph, create inter positive and create coper intaglio plate and then hand ink and print them in an etching press with love. And this these I will call them copper photogravures. Just like other practitioners do.

And as far as the dictionary states:

pho·to·gra·vure (ft-gr-vyr)

n.

The process of printing from an intaglio plate, etched according to a photographic image.

Of course, and you are free to call your prints what you wish. But, as you’ve said in closing, at the very least, a distinction should always be made, with the word polymer included (or copper). I call mine “copper plate photogravures” for this very reason. But I also know of a couple of established artists who simply say “photogravure”, when they are only using polymer. Again, in my view (and others who work with copper, and polymer as well), this is not correct and it is misleading.

At the end of the day though, all it matters is indeed the image, and the print. It is up to a viewer/buyer/collector, to determine whether these distinctions are important, and to many, they are. As an artist, I need to be comfortable with full disclosure. Even from a standpoint of services provided to other photographers/artist, if there were no differences, I should then charge the same amount of money regardless of materials used and that of course would also not be correct, since the cost, time and skills required to work with copper and traditional etching are much greater than just using polymer.

By the way, from an historic point of view, the first photogravures were created by using a screen mesh, with the use of rosin coming later. If it matters, I use Jennifer Page’s analog screens, which are created from actual dust and they are not from image setters. I also use Mark Nelson’s screens, which are image setters and give a deeper etch in the shadows. I also use dust (Picco).

..and I should add, to be clear, that adding this distinction of polymer or copper in front of the word “photogravure” at this point is simply done because of those who insist that there is no distinction. Again, for as much as you don’t like to hear it, photogravure, as an historic process is just it. There are no other methods using different mediums. It is what it is and ignoring this fact is basically refuting history.

The argument between copper plate and polymer photogravure is really no different than the argument that you put forth between digital and film. Both are different and yet both involve similar processes. To argue one is better than the other is equally flawed. While polymer photogravure isn’t etching by chemical acids it is still an etching, and it is still photogravure. Having spent many years in etching studios, everybody still calls intaglio printmaking “etching” as a short hand way of referring to the intaglio process. The ground swell towards healthy, environmentally sensitive and OHS safe working practices is strong. Having worked with both processes personally I find your statement about the polymer photogravure not being a photogravure offensive. It is clearly a safer way to work and is much healthier. Yes it is easier to master and produces a much more accurate reproduction, yes it has differences. A much better distinction is to clearly identify the process when describing either. Copper plate photogravure verse polymer photogravure. Interestingly one commenter identifies one of the most important visual aspects and that is about how the dot grain is formed.

To be honest all true artists I know and admire don’t get so caught up in the processes, but concentrate on the final artwork. Yes they internally debate different processed to decide on which one to use, but they just get on and make finished artworks with the best tools and techniques that they can use and don’t bother with such public displays of this is right and this is wrong.

As someone who chooses polymer photogravure over copper plate photogravure for health, environmental and aesthetic reasons, I am offended that you think I can’t call my prints what they truly are, a true gravure process.

Mr. Metcalf,

I don’t quite understand the defensive/offensive posturing but it is your prerogative.

First of all, I would like you to point me to where I have made a statement that one process is better than the other. And no, the two arguments (if there is even one in either case), are not the same at all. In regards to Photogravure it is simply a matter of what is and what isn’t. I probably don’t have to tell you that the word “gravure” actually means, “etching” or “engraving”. With photopolymer there is only developing and it is an intaglio process. Call it photopolymer intaglio, or call it intaglio, but it is not photogravure. And this is isn’t because I said so, but simply because it isn’t.

I use both processes, depending on the images, or my mood, but I’m also respectful of the historical aspect and differences between the two. Again, it is not a matter of one being better than the other, but they are simply not the same, even though the result is a print of ink on paper.

Therefore, using simply “photogravure” to describe prints made from polymer intaglio is misleading, and, quoting my good friend Paul Taylor of Renaissance Press, who is a renowned gravure practitioner (and polymer as well), also means “riding on the coattails of history”.

Also, to be clear (as I need to be), I don’t get caught in the process. This article is about my use of the Leica Monochrom within the photogravure process, therefore this is what the conversation is about. I use whatever process fits my images and based on my preferences. I certainly don’t let the process dictate what I do, or to elevate my photography to a higher level.

Lastly, you have chosen to use polymer instead of copper for health and environmental reasons and that’s wonderful. I feel that it is an important aspect to be considered and you are certainly free to call your prints photogravures, even though they are not. And by the way, I say this after having made the same mistake myself, but at least I took the trouble of finding out exactly why I was not correct and changed it, as to no mislead anyone, and to respect an historic process and the many talented practitioners before me, and those who are still at it today.

This is also a little excerpt from Jennifer Page at Cape Fear press, another esteemed artist/practitioner who specializes in intaglio processes and photogravure.

WHAT IS A PHOTOGRAVURE?

and other Photo Intaglio Definitions

The goal of this page is to educate people (including artists, teachers, students, curators, collectors and dealers) to the main differences in the various types of photo intaglio printing processes. It is my hope that people will use the appropriate term when describing the processes or medium of these prints. The public already knows too little about these processes so it is important that they are not further confused or misled when looking at prints or learning a process. Correct terms with alternates are in bold for each category.

Fine Art Photo Intaglio Processes

Photogravure (see photogravure plates in the photo below)

Photogravure is a process of etching continuous tones into copper with a sensitized gelatin pigment paper resist (aka carbon tissue) using a continuous tone positive and aquatint screen or dustgrain aquatint. The process was invented by William H. F. Talbot and Karl Klic in the late 1800s for archivally reproducing fine photographic prints. They also employed the use of the dustgrain for its organic grain and fine tonal resolution as well as deeper etched shadows. The tones of the positive are etched into the copper plate in the proportion to the density giving a multi depth layer of ink and a very perceivable and virtually infinite range of tones. Careful timing of the different etching baths also adds another way of controlling the tonal curves. This process yields an etched plate that can be retouched and re-worked with any of the traditional etching processes. The copper plate is often electroplated with iron (steel faced) for printing very consistent and/or long editions. This is still the absolute best way to make a photographic intaglio plate for printing. Photogravure is also referred to as ‘Gravure’ or ‘Heliogravure’ and ‘Heliograbado’ in Spanish. When a drawing on mylar is used instead of a photgraphic positive the print is known as a ‘Direct Gravure’.

Photo Etching

Photo Etching is a process where a metal plate, usually zinc or copper, is coated with a high contrast, negative working photo-sensitive resist such as KPR or sensitized fish glue or a thin film photopolymer such as Puretch. The photo resist is exposed to a very fine halftone positive or line image. A halfone creates an illusion of tone by using tiny black dots of varying size and distance. Halftones can be made digitally now with inkjet or laser printers. If an aquatint is required it can be done traditionally with dust or spray, built in digitally or with a screen exposure. The plate is developed with a solvent or mild alkaline producing a high resolution etch resist. This process yields a plate that can be etched to the desired depth and tone. In photo etching all of the exposed plate and dots will receive the same amount of etch unless manually staged out by the artist. The resist is usually stripped before printing and the etched plate can be retouched and re-worked afterwards with any of the traditional etching processes. Some artists are using gelatin pigment paper (see Photogravure above) for exposure and etching of fine halftones. Because of the nature of etching a halftoned image, these prints should be called ‘photo etchings’ and not ‘photogravures’.

A Photo-Etching can also correctly be labeled as simply ‘Etching’.

Photopolymer

Photopolymer is a non-etch process of making a photo intaglio printing matrix. Plates are either manually coated with a thick photopolymer film such as Imagon or Zacryl or they are available as pre-coated flexographic printing plates. These pre-coated plates are known as Printight by Toyobo and Solarplate. They are either singly exposed with a very fine halftone that has a grain already built into the blacks or they are exposed with a continuous tone positive which requires a separate exposure to an aquatint screen. The plates are developed in water or a mild alkaline solution which washes away the unhardened photopolymer creating fine recessed crevices for the ink. The final print can sometimes appear quite similar to a photogravure print except the process is significantly different and lacks the subtle tonal range of a good gravure, especially dustgrain gravure.

The ‘Photopolymer Intaglio’ process is often incorrectly referred to as ‘Photogravure’, ‘Photopolymer Gravure’ or ‘Polymer Gravure’. The inclusion of the word gravure here is misleading since there is no etching or engraving involved, there is only developing. ‘Photopolymer’ is also correctly known as ‘Photopolymer Intaglio’. These descriptions can also be used when positives are hand drawn on mylar.

A print made with any of the processes above could be called Photo Intaglio or simply Intaglio but when the description is more specific then the term should accurately reflect the process used.

We seem to hear lots of comments about how the photographic print is dead these days, but I have always considered that the print, including inkjet, makes the photograph, and is a very important part of the craft of photography. Maybe I am old fashioned but looking at a photograph on a screen, which is contained as a digital file on a hard drive, is not the same thing at all.

I would love to see your photogravure prints for real, Max, as it is a beautiful process which you have obviously mastered, but alas I am in the UK and far from New York.

Your photograph titled “Strength and Grace ” is absolutely gorgeous – just love it.

Best wishes.

Andrew

Thank you, Andrew! The prints is dead? Yeah, you’ll hear that, just like vinyl is dead. I’m still buying vinyl like crazy and when I want to sit down and actually listen to music, looking at the cover, reading lyrics, that’s how it’s done. I guess I’m hopelessly romantic 🙂

If you ask me, there is nothing until there is a good print. Now, of course, this applies to images worth printing, for those who are actually interested in crafting art, for pleasure, to sell, whatever. Good images that exist in a vacuum, on a computer screen, are wasted, in my opinion. Is collecting “like” on Facebook or bluebirds and pink balloons on Flickr what is all about? Is meaningless ego stroking what we strive for?

I always say this to anyone willing to listen because I believe that we are in deep poo poo if we let the art of print making die off. Also, for artists who may be interested in passing on a legacy, and sell their artwork, who is ever going to pay anything for a digital file on a screen? I’m sorry, but there has to be a tangible product that gives a buyer value and something to hold onto.

I buy prints whenever I can, from established artists and some not so. Looking at a computer screen does not hold the candle, ever. I’ve recently purchased a few prints of Fan Ho, from Modernbook Gallery in California. They brought tears to my eyes and I get the chills when I hold them, they are so beautiful. No image on a screen can do that.

Interesting article. IIRC, some professional photographers also shot on digital, then with the help of a professional lab creates 35mm digital negatives that are used for archival or silver-gelatin prints, having the “best of both worlds”.

Yes, I believe Ilford offers such services for those inclined to use them and don’t have or want a darkroom.

Having read this I now am more convinced than ever that I really do want to get a Monochrome Leica.

If you want an MM, get an MM.But this has nothing to do with the content of this article – that is CLEARLY about a competent photographer that has found the right tool for his craft. This tool could be, ideed, VERY different for another photographer. You could find that an RF is not bringing to you an enjoyable user experience and that you’ll be better out with an MF digital camera. Or a full-frame DSLR… Who knows?

Yes, this article could have easily been titled “The Nikon D800 and Photogravure” so I explain briefly my point of view. The camera, as always, is nothing more than a tool. Use what you like, what you can afford, and what fits your style. At the end of the day, what’s between your ears is what makes all the difference. So, why the Leica Monochrom? First of all, I did not get in depth into the camera itself here, because there really is no point in another “first hand impression” or review for this camera and really, that’s not what it’s about.

My choice is simply due to the fact that I’ve been shooting Leica film camera for a long time, I have a bunch of great old lenses, and that’s what I like for a number of reasons. The Monochrom is interesting because in many ways, the workflow resembles shooting film. There is no color, I still need to use filters in front of the lens, and the files look in most cases like negatives that need work in the darkroom to bring out a good print. It’s a choice one has to make while considering a variety of factors (aside from “I got money and I just want one). It is a very expensive camera, especially when slapping a new lens on it, and there are other cameras out there that can get the job done for a tenth of the price. I was able to justify its use and expense by marrying it to a beautiful 19th century process, to produce gorgeous prints that I am selling. If I was just posting on Facebook, Flickr, or any other purely digital environment, without selling prints to recover the expense, I would see no point in owning it. Again, it’s a choice one has to make, and everyone’s mileage, of course, may vary.

It’s a testament to the quality of the images themselves that you’ve captured and shared, that you’ve convinced us of the potential quality of photogravure prints . . . without ever showing us the prints! How ironical. It makes me want to see the prints themselves which must be much more beautiful. All this raises the issue of how you got the photogravure prints back into digital images to share on this blog.

I agree, Larry. Unfortunately, this is the world we live in. I frankly can’t stand how art is consumed today and I encourage people at every chance to visit galleries, shows, museums, and of course BUY PRINTS. That’s what I do and there is no better way. The only thing this screen gives us is an approximation at best but it ain’t the real thing. The prints were sadly scanned with an Epson 10000 XL 🙂

More importantly, if anyone is in the NY area, my photogravure show at the Lionheart Gallery in Pound Ridge, NY is up until November 1st.

I read your article with great interest, Max, especially when I noticed you commented on Jon Cone and his Piezography system which I use with a converted Epson R2400. I plan on reading your article again and visiting your website and the photogravure.com. After years of shooting for publication, I am now retired and looking to slow down a little and see what I can do with a more deliberate approach to my photography. Thanks for sharing your work and thoughts!!

Thank you, Rich! Jon is a great guy and surely does a wonderful job with those inks. For me, it’s as good as inkjet gets. Used it for a while as well, but I like to get my hands dirty 🙂 But he’s happy to sell me the inks to make my digital negs and positives. I hope you enjoy your retirement and I’m sure it will be conducive to slowing things down and picking up a little analog approach. Rule #1: don’t forget to have fun! 🙂

Simply stunning photography, Max. Clearly, the Monochrom and photogravure are made for each other.

Thanks so much, Doug! The monochrom sure is a capable camera. Not sure if anyone would notice if one of those prints started as a D800 file, but I am just not a fan of DSLRs 🙂

I own both the Monochrom and a D800E. Both are fantastic cameras, but each brings its own characteristic look to the table. And like anything else, neither will always be the best choice for shooting everything.

I’m sure, Doug. At the end of the day the camera is just a choice. Both will do a fantastic job, albeit in different ways and looks.

Max,

Good to see you back on Steve’s blog.

All you articles here have been inspiring.

Your photo’s bring an atmosphere that seems difficult to reach digital only indeed.

Apart from your technical skills and the excellent framing, these photo’s also show compassion with the subjects.

To me you showed again it’s more satisfying to create one photo that really stands out than one hunderd photos that are just good. And that requires a lot of perseverance and patience.

These photos are extremely good. Congratulations!

Thanks so much, Jaap..and good to be back here for some good conversations! I much appreciate the comments on the images. What you see, is what I feel. I believe that a good image is born from one’s soul, with the eyes allowing us to see it and the camera to capture it. Sure, there are some technical aspects to be considered but I leave most those for the people who try to emulate Ansel Adams :)) Digital…what can I tell you? 🙂 Again, for me, in a vacuum, living on a hard drive, a screen and an inkjet print at best, it’s a waste. Of course it’s just fine for wedding photographers, journalists, or simple sharing, but there is a lot more that can be done with it now, with a hybrid workflow, to create something special.

I live near Cone Editions and I regret not taking one of his workshops when I had the time. My early attempts at making digital negatives were awful. I’m happy to see yours are nicer.

Gordon, Jon Cone is still offering workshops quite regularly and he’s perfected digital negatives quite well lately.

I spent five years doing my apprenticeship in printing and was lucky enough to learn about [and practice] Letterpress; a relief process, Gravure; an intaglio process, Lithography; a planographic process, and also Silk Screen, Flexography, etc. All processes able to render photographs onto a desired substrate. It brings nothing to the forum if some people are going to try and pass-off cheap reproduction as something genuine, and makes a mockery of those who work fastidiously and hard at producing truly inspiring results using techniques and methods [and old tools and materials and equipment] to create real art and also the unwitting purchasers of said ‘art’. Cheating, by calling one process another, is a debasement of the years of history of tradition, built up since Guttenburg, Caxton, Senefelder, Miller, et al. Max has made some fine photographs and turned them into staggering prints. Let’s enjoy and celebrate that!

Thanks so much for the very kind words, Thomas. Glad to meet like-minded people who appreciate and understand all the work that goes into producing good art and prints. Historic processes should be cherished, skills should be learned and passed on. If we allow all of it to die, for the sake of convenience and the need to feed our instant gratification hunger, so much will be lost.

One thought that I always stretch to any photographer/artist, novice or pro..THERE ARE NO SHORTCUTS.

Thanks for such a great article Max – and for your explanations in the comments too. I would also love to see a part two, as I could just go on reading and looking at your lovely prints.

Thank you so much, Brett! Glad you’ve enjoyed it. This is a work/project in progress, so there will probably be a part two.

I use to be a Gravure Printer and wordked a lot with copperprint, but in former day’s there wasn’t much need to get rid of the chemicals in a good way, just pooring down the drain so to speak, how do you deal with them nowaday’s ?

Well, it probably hasn’t changed much in that department. I don’t have a lot of waste but a little dichromate does end up down the drain. The bulk of it gets neutralized first and then dumped. The acids, when exhausted, get picked up. Ferric chloride is not a big deal though, but it is corrosive to metals still, even when well used.

This is exciting! I’ve read about this process for years in some of my very old photo books.

So glad to see this!

Happy, you’ve enjoyed it, Peter, and thank you!

FYI…I did post replies to Pavlos and Richard Greenstone, but they included links and it seems like they are awaiting moderation. Steve?

Max, these images are truly wonderful regardless of how they are captured. I am an analog/darkroom photographer and I agree that the craft is as important as the art to me. Polymer photogravure is on my list of things to try, but perhaps copper plate might be worth a go…..all I need is a press and a proper inkjet printer and a whole lot of plates and paper! Thanks for the inspiration.

Thanks so much, Mark and glad to meet more darkroom rats 🙂 Polymer is wonderful as well. My only complaint is that the prints sometimes look almost..too good..smooth 🙂 Kidding aside, some imaged benefit from that process better than copper etching but at times they can also look a little sterile. I always say that prints from copper etching look more “organic” to me, if that’s the right term 🙂

Either way, it’s a blast and the printing process is the same as with copper, although the polymer is flimsier and harder to handle.

Hey Steve,

Photogravure is by far a beautiful finished process. I did my time in the early `70s in all the Photo Printing processes. (all) The one thing that we need to keep in mind therefore, are two points on what one needs to keep their eye on.

They are:-

1) Optical dot gain.

2) Mechanical dot gain.

Watch your shadow areas!

This is extremely important and your mates doing these prints will explain, if you don`t already know. However, the result for photography to print is the best without doubt and I still look through my old `50s photography books printed in the gravure process. (ah.. the good old days)

As well as the most beautiful result therein, the feel to the finger tips is unbelievable.

Not the easiest, cheapest nor the cleanest of processes, however as said earlier, the most beautiful in a fluid kind of way.

Good on you guy`s for reviving this processes.

Bruce. (just another old shutter bug).

Yes, Bruce..nothing like it indeed. Not easy, or clean but hey..no guts, no glory 🙂

Truly artful images and worthy of the process. I guess I can say you give good punctum! That first image is a classic.

Thanks so much, Donald!

This is by far the best guestpost in this blog since I read it. And that’s right from the beginning! Your pictures transport a feeling, I like them very much!! The only counterpart I want to say is that it is rather easy to produce large negatives, – by classical enlargement. Just my two Cents… :-))

Thank you for the very kind words, Alex. Large negatives? Yes indeed. But positives for the gravure process not quite so. There is really little film of consistent quality available now for that purpose. All gravure practitioners have now switched to digital positives and I don’t know of anyone still working with film for this purpose. For negatives, and large format shooters doing platinum, this is of course a non issue, even though many of them are also now working with digital negatives. At this point the quality is good enough so might as well put some digital workflow to good use in the analog world 🙂

Thanks for your answer. After reading a bit in some old books about the platinum process I have to agree with what you said…..

Go on with your wonderful work! Wish you all the best.

Thanks for a really insight in the process of making photographic prints at the highest standard ever. Wants me try harder and go further on making images…. ( -one of those impatient amateur)

Thank you very much, and very happy to hear that you find it inspirational. That’s what it’s all about!

Awesome is an over-used adjective, but I can’t think of a better one. The eye and taste being even more impressive than the beautiful printing which is surely even more impressive in real life!

Thank you! Much appreciated. Glad you have enjoyed the article and my work.

Well Max, these are stunning. Love it. I have owned the MM for 4 months, which is my first experience with a rangefinder. As a camera is it’s been very very different and very very enjoyable and am learning every day I use it.

I’ve recently taken some images and you have inspired me to look into this way of creating prints more closely. I have a few I’d like to make into prints and not just live in a hard drive!

thanks for the inspiration!

Thank you, Andy. The Monochrom requires a little getting used to in the exposure department, as I am sure you have found out, but it certainly is a capable camera. Still, like I said above, It’s a VERY expensive toy 🙂 Hard FOR ME to justify the investment unless I could bring out something worthwhile and tangible with it and able to sell the work. As far as printing, well I’m happy to create some enthusiasm that goes beyond simple file sharing and inkjet printing. Again, and I want to stretch this, inkjet prints can be absolutely stunning, especially with Jon Cone’s Piezography inks, but that’s not my preference. I’m not knocking them, but I simply prefer analog prints and a hands-on approach.

If you really wanted to take it beyond inkjet, I also highly suggest photopolymer, as it is an easier process to master. Of course platinum/palladium or gum over platinum are certainly worth learning as well and they don’t require metal etching, or a press

Excellent work

Thank you, Danny.

B-b-but last year you were telling us, Max, that NOTHING is as good as film.

“..Over the past year, while still dedicated to film photography and silver gelatin..” ..you’ve now decided that digital photography, with a Monochrom, DOES beat film.

Maybe next year you’ll tell us that “photogravure is SO 2013..” and you’ll advise shooting in colo(u)r with a Leica M, and printing with a multicolour laser printer. “..Laser has so much more depth than gravure..” etc.

Perhaps your predicament is that you’re a “late adopter” with an emotional attachment to old technology while secretly wanting to use tempting new technology

But you’ve now jumped on the bandwagon, Max; welcome to the 21st century!

I think that you’re misunderstanding everything here, David. I shoot film, 99% of the time and for me it is my medium of choice. I simply found a use for the Leica Monochrom in analog environment. I print analog, I work in a darkroom, and I get my hands dirty. Bandwagon? Which one? I don’t follow you. The camera is a tool. I’m using one (along with film Leica, Rolleiflex, Large format, etc) that happens to give great results when used in combination with 19th century printing process. Heck, it’s great for platinum work also. Seems like you’re trying to start an argument out of nothing.

Don’t let your feathers get ruffled Max; David is only yanking your chain. If his remarks were aimed at me, I would say/think: So who says I have to be consistent?

It’s all about the image, and these are wonderful.

Indeed, Michiel 🙂

This does raise another question though. Have you tried any other digital camera for this purpose besides the Leica M Monochrom? If so, there are some of us that might want to hear you opinion about any differences you may have encountered.

Larry,

No, I have not, since I have sold my D700 a few years back. Differences? I’m sure there would be, but again for me it comes down to making choices. Any camera will work of course, and old Leica lenses can give a rendering that is different from new ones, or Nikon, Canon, Fuji lenses, etc. I mostly use an old 35mm f2.8 Summaron, a first version Summilux 50, a Summitar, and sometimes a Summar as well.

That is one of the best articles here! Max is there any video or book explaining the technique? Thanks for sharing that with us! BTW great shots 🙂

Thanks so much, Pavlos. As I have suggested above, a great book is “Copper Plate Photogravure – Demystifying the Process”. I believe it is available on Amazon but probably used.

I did make a quick and informal video of me making a print a while back. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T3PyIV5yLkA. It doesn’t show what comes before the printing stage but Paul Taylor has also a good video on his website here: http://www.renaissancepress.com/?page_id=72&template_id=5&preview=true

How is the transfer from the digital to positive film made?

KB…basically, you work your image in lightroom or PS, doing all your work as you would normally do, making sure that you have no blocked highlights or shadows, preferably. Once that is done, a contrast curve has to be applied to make the positive fit into the density range of the sensitized gelatin tissue. This process of “linearization” to arrive at this Photoshop contrast curve requires quite a bit of work and I would have to write a small book about it. Once the positive is ready on the screen, it is then output to an Epson printer (in my case a 3880 loaded with six shades of gray, K7 inks from Jon Cone’s Piezography system) and printed on Pictorico clear film. After drying for a minute with a blowdryer, to get the ink set, it is then ready to be exposed.

Thanks so much for sharing this. I think the length and content, especially the photos–sometimes there are not enough of them–is just right for this kind of blogger format, mainly because it allows for us to get more via Q & A. You just answered my first question: how do you get from the digital image to the positive slide. After reading your answer, it occurred to me that this process has much more fidelity/integrity than you get from going to film negative to digital file via a scan, which as we all know is another type of digital camera. Is this the same process you’d use to make a silver gelatin print as well?

I already have a copy of the Camera Work book you recommended. What an incentive to read through it again.

My pleasure, Larry. It is indeed fun and stimulating to have these conversations, sharing ideas, opinions and tips..as long as it remains civilized on course 🙂

Well, this is a bot of a quagmire, honestly. Film can have a look that it’s very hard to replicate with ANY digital filters. They can look great, but they are different and they are approximations. Plus, once we get into medium, and certainly large format, comparisons really go out the window. Now, scanning film with consumer scanners can be okay, but I’ve seen scans from pro drum scanners and again, big differences. So, as far as photogravure, for a 35mm film shooter, makes little sense. Why? Because in essence, the process is what creates the final print and its own look. The “filter” even when applied digitally, means little. Sure, you can add grain, and that’s ok, but there is no need to go crazy. For photogravure, just set the image on the screen the way one wants it to look on paper, but in the end, the contrast is achieved and controlled with etching, and also use of inks, and wiping techniques. Scanning film correctly is not quite as easy as most people think so, for me, it really makes sense to go through all the trouble for medium and large format. Then again, the Monochrom can output files that can rival medium format. Having said that, the Monochrom DOES NOT give the same look that my Rolleiflex 2.8f with an 80mm, loaded with Tri-X and cooked in Rodinal will give me. Not in a million years. So…choices..

For silver gelatin, I still work with an enlarger. I have done digital negatives on occasion but mostly for the lith printing process. For straight up silver, I’m not that keen on it. Although, again, digital files from a digital camera printed on silver still beat inkjet in my opinion.

Well, these images would look good in almost any technique! And they certainly show the point of the MM even just being looked at on a screen. In the flesh (?), they must be quite stunning. I also want to hear more about that photogravure technique – so a second article or some referneces would be nice. A minor comment: I also use that way of framing my black and white prints – white with a thin black frame. Thanks so much for sharing.

Thank you very much, John! I did not want to get too technical about the process, as I was afraid it would get a little long winded..but maybe I should have. Of course, there are many references on the web about the process, but one day I will probably write more about it and make accessible to this audience.

Great stuff Max!

Cheers,

Michiel

Thanks, Michiel!

Wow, these are great! I am totally going to print these out on my inkjet printer (using tried-and-true copy paper, of course) and scotch tape them to the walls of my cubicle.

Just kidding. C’mon, deep down, you know that’s funny!

Go for it! 🙂

…And the Past is in the craftsmanship one can almost “smell” in your images and the hankering for their tactile sensation.

Thank you very much. I will be visiting your site every day.

Thank you so much, Artur. It is indeed quite special to hold and look at these prints in person. And by the way, they do smell good also, since I use a few drops of clove oil in my ink mix 🙂

AMAZING article and words, STUNNINGLY beautiful pictures. Probably the best work I’ve seen here, in a very long time.

Thank you very much, Stéphane! Much appreciated.

Max, thank you for a wonderful article and stunning photographs! I purchased my Leica M Monochrom for exactly the same reasons. I used to print in the darkroom and painfully made the switch to digital printing ultimately using an Epson 3880. I am aware of the photogravure process which I believe Alfred Stieglitz used to produce Camera Work. Can you recommend any good books on the photogravure process? Do you or do you know of anyone offering workshops? Thank you again for a wonderful article.

Richard – You should find everything you need to know on photogravure.com.

Not everything, Mark…since I ain’t in there yet :)) Just kidding..I know…

Hello Richard. Thank you!! The Epson 3880 is a great printer, and I what I use to print my digital positives and negatives for silver or platinum/palladium. There is a lot these printers can do, at the service of the digital photographer who wants analog output on paper. Yes, Stieglitz and Camera Work was how everything began for photogravure, as far as a wider audience. Steichen and Strand of course also produced incredible work and they were prominently featured in Camera Works numerous times. As far as books: “Copper Plate Photogravure – Demystifying the Process” is a good one. Not cheap if you can find it, but great. This is also a must have, for reference work. http://www.amazon.com/Stieglitz-Camera-Work-Pam-Roberts/dp/3836544075/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1380745784&sr=1-1&keywords=camera+work

As far as workshops, I will probably offer them at some point but not until I can expand my studio. I highly recommend Paul Taylor at Renaissance Press in New Hampshire for that. He is my friend and mentor.

Thankyou Max, just purchased both books.. Let me know when your coming to the UK !

all the best. Mark Seymour

Max: Its a honor to see your extraordinary work, as a result of your eye and skill regardless of what camera you would use….. D.

Thanks so much for the kind words, Daniel. Happy that you’ve found my work interesting.

Indeed, these are ‘stunningly’ beautiful prints. And, absolute evidence of this artists affection for the process that requires the obvious skill of a truly serious photographer and artist. Therefore, allow me to applaud the talent of this photographer and this darkroom artist.

Whilst I have only praise for his work. I would personally find it too time consuming and labour intensive. And, being impatient as most of us in this generation have become, the push button ease printing of my own photos on my Epson 3880 will take precedent (for me) over the equipment, chemistry and labour required in this authors work.

Nonetheless, I can only add a loud ‘Bravo’ – to his achievement.

With respect, Norwin

Thank you so much for the kind words, Norwin. Oh yes, we have indeed become the “instant gratification generation” 🙂 Sometimes it’s a good thing and other times..not so good. At the end of the day, we all do what makes us happy…hopefully 🙂

This is certainly the most intelligent and otherwise best guest post ever on this blog site, Steve. I only wish the article was more detailed and about four times longer. Thank you for posting and thank you Max. Peace.

Well, Max never disappoints 🙂

Don’t know about that, Steve. I do try hard though 🙂

Thanks so much for the kind words! Could have written a lot more but didn’t want to bore anyone 🙂

Agree: this is intelligent, and links with the current difficulties we have with printing at high quality.